Eqqo Switch Review – Taking Care of That Egg

Eqqo is a narrative-heavy puzzle game inspired by the ancient myths and stories of Ethiopia. You play as the guiding hand of a mother as she tells the tale of her brave but blind son, interacting with the world as he goes in order to help Eqqo traverse and overcome its dangers. It’s a game with some awkward mechanics and control issues, but one with a narrative that’s so strong and so perfectly executed that it ensures a true lasting impact.

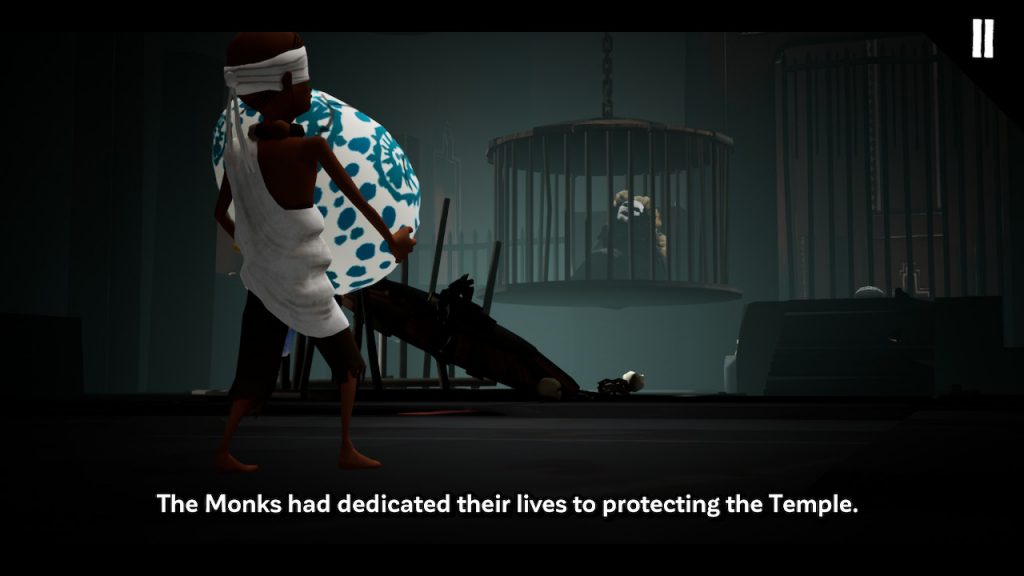

The game begins with the soothing voice of a mother, accompanied by captivating animated paintings that bring to mind the Ghibli movie Princess Kaguya. The mother tells us about her son, the titular Eqqo, who was born blind but loved to hear tales of myths and legends. These legends, as well as the world we’re in, are inspired by Ethiopian myth. This is a hugely underexplored area of world mythology; and getting to discover it through this game is a true thrill and an absolute pleasure.

Eqqo’s favourite myth, she tells us, was about a serpent god who came down to lay an egg in an ageless tree known as the Mother Tree. In the narrative of the game itself, Eqqo has disappeared from his mother and soon finds the serpent god, but she is wounded from attacks by human aggressors. And so, Eqqo takes up the egg to finish the story himself. From here, Eqqo must keep the egg safe while navigating puzzles and moving forward, heavily reminiscent of the PS2 game Ico.

The way that the game introduces us to a simple Ethiopian myth and then lands us with a poignant message about humanity’s greedy abuse of the land and its creatures hits the player in a very affecting way. And while the message of human corruption versus the peace of nature is nothing new (We all made the same joke when James Cameron released Avatar), a story’s success often comes down to its telling, and the mechanical telling of this story is so pitch-perfect that it carries the weight of that message perfectly.

It’s not all perfectly in sync, however. The game is narrated by the voice of Eqqo’s mother telling us of her journey. Her lines drop hints in a fairly unawkward expository way, but they do cause some jarring narrative moments, such as one single line where she refers to the boy as “my son” but then says, “his mother was wiping her tears”. The fact that the mother is both our disembodied, omniscient narrator but also the worried and helpless woman who has lost her wandering child makes for some awkward dissonance that permeates the game’s narrative. It’s not a large issue but it is consistently awkward.

That being said, the mother being the narrator works both narratively and mechanically far more than it doesn’t, and the charming poetic quality to her dialogue is sweet and warm in a manner reminiscent of myths written for children. In one early scene, Eqqo slips between thin bars, leaving the egg behind, and the mother remarks that, “Sometimes it’s good to be shaped like a blade of grass.” Playful language like this, which is informed by actions and mechanics performed in-game, really add to the storytelling atmosphere of the game in a joyful way.

You play as the hand of the mother narrator guiding the character of Eqqo from area to area. Each area or room is a traversal puzzle that must be solved by interacting with the world around you. Half the time this involved you, the narrator’s hand, moving things like levers or cogs to unblock the way for Eqqo to move forward. Other times it requires you to tap on something for Eqqo himself to interact with it, like a pressure pad or a switch.

The quirk of being a narrator guiding a character through their story is a compelling and effective one, especially when coupled with the almost constant voice of the narrator telling the story as you go, but the fact that the protagonist is a blind child might elicit a few nervous or awkward giggles from you, the player, as he bumps into a wall on the way to a switch. This bumbling around cleverly reinforces the theme of motherhood as a watchful eye and a guiding hand, but it does also sometimes come off as unintentionally awkward.

The game is roughly four hours long, and during that time you’ll move at a decent click from puzzle room to puzzle room, interacting with the environment to help Eqqo along. The game does a decent job of introducing new interactive elements bit by bit, but there’s also this sense that the game never stops being a tutorial. New mechanics are added often, and they’re all very instinctive and easy to figure out, but the game never feels confident in letting go of your hand and encouraging experimentation. Despite this, the way you interact with the rooms, and with Eqqo, is never unsatisfying.

The puzzles are very easy, however. Rarely did I feel stumped by a puzzle. This is disappointing on one hand, but it also means that the narrative is always moving forward. Eqqo is far more an interactive story with puzzles than it is a solid puzzle game, and that means the focus is on keeping the narrative flow, and that’s totally fine. It serves the story perfectly.

What does make the game difficult at times, however, is the way the camera and cursor are operated in the game. Eqqo plays quite differently if you’re in docked or handheld mode, and the game is clearly designed with a touch screen in mind. I started playing it in docked mode, where you must use the left analogue stick to move the cursor (narrator’s hand) around the screen. Then I switched to handheld and found the touch screen far quicker, and at times less awkward, to use. However, each mode has its drawbacks. In docked mode, moving the cursor is slow and clunky, and though you do get used to that pace, sometimes you must react to a scenario quickly, like when Eqqo is in danger and the cursor just doesn’t move as quickly as you would if you only had to tap the screen.

However, in handheld mode there’s a big issue with visual focus. The game has this delightful detail of playing with focus when something is near or far, replicating the human eye really well. When you use the cursor in docked mode, the focus reacts perfectly. In handheld mode, however, the focus drops and becomes permanently fuzzy unless you occasionally wiggle the analogue stick to wake up the cursor like you would a screensaver. Narratively, it’s as though our storyteller has lost her focus. Another problem with handheld mode is that the game uses the Switch’s gyroscopic controls to move the camera around. But the camera can also be operated with the right analogue stick, which is much more precise and less nauseating. However, the gyroscope cannot be turned off; there is no options menu in-game that I could find.

All of this summed up, it’s actually better to play in docked mode without the touch screen, despite the touch aspect being more responsive when it comes to interacting with the game’s puzzles. It’s a shame because the touch screen works with the narrative theme of being a mother’s and storyteller’s guiding hand so perfectly. But camera issues mean that docked mode is simply a more stable way to play.

Eqqo runs smoothly however you choose to play it. There are no issues with framerate, and the game’s aesthetic means you always know exactly what you’re doing. This is key to a good puzzle game. Eqqo also has a lovely color pallet of bold greens, blues, browns, and whites that is so soothing and warming. It provides us with a charming storybook world that is a true joy to live in for a few hours as the story is told to us.

Speaking of being told a story, one of Eqqo’s true highlights is its narrator’s voice. Almost constantly, she is telling us the story of Eqqo’s journey through this world. The story, as mentioned before, is based off Ethiopian myth, and the voice actor playing the narrator does such a pitch-perfect job of conveying this tale to us with a calming voice that hits all the right notes whenever danger lurks or safety is found. Her voice also pairs perfectly with the beautiful fairy tale writing that’s full of playful mischief and silly metaphor.

Going hand-in-hand with the narrator’s voice is the game’s soundtrack, which was actually recorded by the Prague Symphony Orchestra and is truly phenomenal. The only problem is that it’s quite minimal. This could be due budget restraints, but it means that the game is more silent than it is not. When the orchestral tracks play, they are intensely beautiful, but they are often separated by long gaps of silence that are filled only by the narrator’s voice. Fortunately, this does mean that the game is never quiet since she is talking almost constantly, as well as reacting to every move you make. Overall, the orchestral soundtrack and the narrator’s voice pair together to make one of Eqqo’s strongest aspects.

Eqqo’s value can be judged in two ways: on its length and its impact. Eqqo will take players around four hours to finish, and while that doesn’t feel long it does also feel like any more would have been padding. It’s a shame that the game’s puzzle mechanics aren’t a little more challenging, but that also would have ground the narrative to a halt and doesn’t feel worth the trade-off for such a compelling and charming tale.

This is the impact of the game. The color and visual tone of its world, coupled with its writing and the soothing prose of its narrator, creates an experience that really sticks with you long after the story wraps, in the exact same way a good book does. It might not be an overly long experience, and it might be one with some frustrating controls, but it is an affecting interactive narrative that will leave a mark. Replayability is really down to you, but I can see myself wanting to spend a few more hours in this world down the line on a rainy Sunday afternoon.

Eqqo Review provided by Nintendo Link

Developer: Parallel Studio

Release Date: Feb. 7, 2020

Price: $6.00, £5.40, €6,00

Game Size: 699MB

Outstanding music and voice acting

A vibrant realization of Ethiopian myth

An engaging, interactive world

A poetic script with a beautiful story

Clever fusion of mechanics and story

Awkward and dizzying camera controls

Simplistic puzzles

A little on the short side

What's Your Reaction?

Will Heath is a freelance writer and digital nomad from the UK who mostly splits his time between London and Tokyo. He runs the website Books & Bao – a site dedicated to international literature and world travel – and writes about video games for Nintendo Link and Tokyo Weekender.